TALENT MANAGEMENT AND THE DUAL – CAREER COUPLES

I learned that the company still had not figured out how best to manage the growing number of its employees who want to advance but also care deeply about their partners’ careers. I also work closely with the heads of talent and learning at companies that send executives to the management program I codirect at INSEAD. Today, in almost half the two-parent households in the United States (compared with 31% in 1970), both parents work full-time. Still, companies struggle to anticipate and mitigate the effects on their talent pipelines.

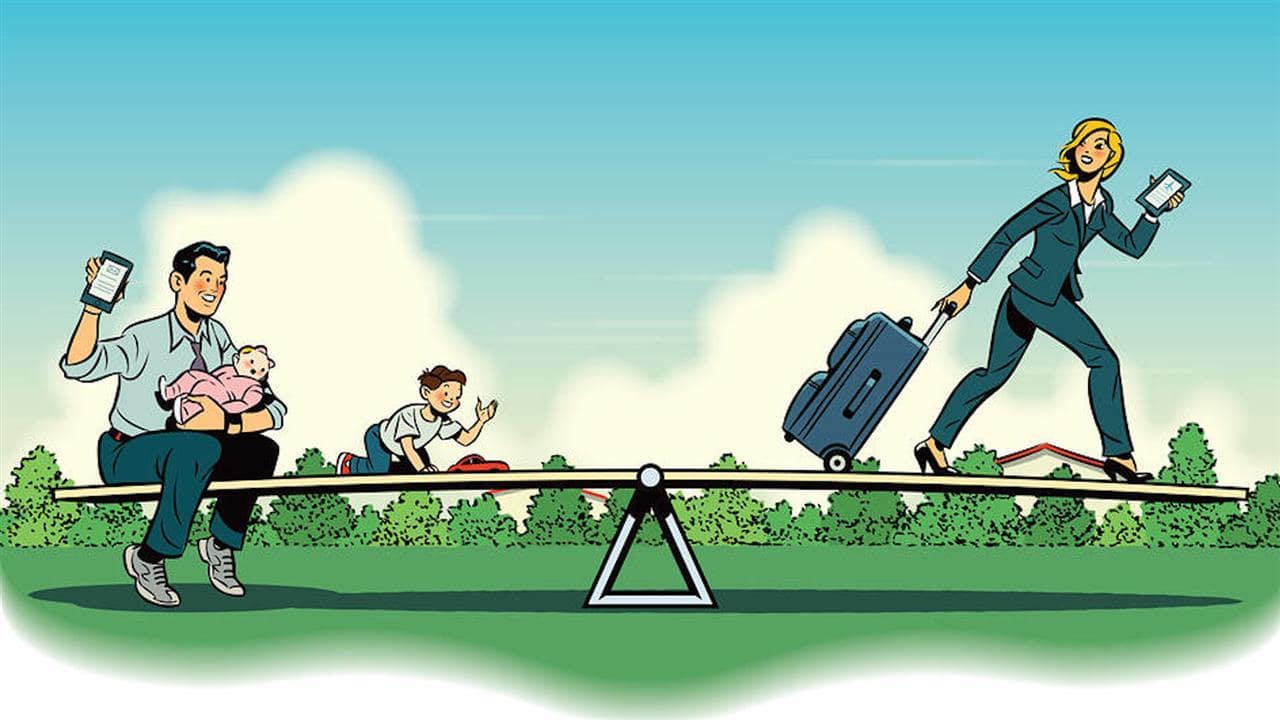

The crux of the problem is that companies tend to have fixed paths to leadership roles, with set tours of duty and long-held ideas about what ambition looks like. That creates rigid barriers for employees—and recruitment and retention challenges for their employers, many of whom are failing to consider the whole person when mapping out high potentials’ career trajectories.

The Trouble with the Usual Talent Strategies

Although most companies deny having traditional career ladders, executives in midsize and large organizations are widely expected to cycle through a variety of divisions and functions en route to the executive suite. This talent-development model usually involves multiple relocations. It originated in the early 1980s, before technology had opened the door to efficient, productive virtual work. For the most part, talent was “unbounded” (my term). That is, spouses didn’t have competing careers, so they managed home and family life, freeing up executives to meet their companies’ demands.Times have changed, of course, but most talent management programs are still designed as if every couple had a dedicated homemaker and the internet didn’t exist. Members of dual-career couples understand that they’ll need to make multiple moves across functions and geographies if they want to ascend to senior roles—and they’re not averse to that. But having to drop everything and move at a moment’s notice forces them to choose which partner’s career will lead and which will follow. These days, fewer couples are willing to make that trade-off.

The mobility challenge is exacerbated when organizations expect several moves in a short time frame, which is not unusual. At one global chemical company, for example, a new management acceleration program moves people through three functions—and to three locations around the world—within a year and a half. “This rounds out participants’ experience and knowledge in an efficient way. But, she added, “it certainly doesn’t work if you’re in a dual-career couple or for anyone who doesn’t want to drag their family around the world….So it stops a lot of great talent from even applying.”

Most companies assess executives on potential as well as performance—and people who don’t want to move are dinged on potential, because they’re perceived as lacking ambition. Thwarted advancement is the most likely outcome, particularly for junior and midlevel managers. But at senior levels, where fewer lateral moves are available, there’s a great deal of pressure to “move up or out.”

Every family has tasks that must get done—buying groceries, making meals, taking the car in for maintenance and repairs, driving children to and from school and activities, and so on. In traditional couples, the noncareer partner assumes the lion’s share of these responsibilities. For dual-career couples (even those who can afford to hire help), managing all this on top of work is a constant juggling act. As I studied these couples, it was clear that they do not want to work less, but they do need to work smarter and more flexibly.

The irony is that research has shown the benefits of flexible working—for instance, improvements in efficiency and knowledge sharing. And in my interviews I’ve found that an organization’s commitment to cultivating and valuing flexible work is a key draw for members of dual-career couples. HR teams are well aware of these advantages. That’s why they put flexible policies in place.

If companies know what works in theory, why do they keep reverting to their old ways of managing and grooming talent? People at the top tend to think, “Well, if I did it, so should the next generation.” It can be hard for them to identify with dual-career constraints if they came of age in a different time and never faced those constraints themselves. Because the current crop of high potentials aren’t willing to sacrifice their partners’ needs, a bit of a stalemate results—and mobility and flexibility challenges go largely unaddressed.

Over the past three decades, assortative mating—the tendency of people with similar outlooks and levels of education and ambition to marry each other—has risen by almost 25%. Nowadays, when an organization hires a manager in his or her thirties, that person’s partner is also likely to be an ambitious professional with a fast-paced career. Paradoxically, a trend that should expand the talent pool for companies shrinks it instead, because of their outdated ways of developing people.

A New Talent Strategy

Organizations must stop worrying so much about where aspiring leaders serve their time and instead focus on the skills and networks to be acquired. The talent management director of a global engineering firm described her company’s approach like this: “We have a list of experiences that future leaders need to have, but they are location-agnostic. For example, managing a business in crisis or doing a turnaround—sometimes you don’t have to move at all to get these experiences.” That’s a departure from the days when the company’s CEOs believed that one had to work in set locations to move up. Shifting the focus from “where” to “what” opens a range of creative solutions, such as brief job swaps, short-term assignments in various organizations or units (sometimes called secondments), and commuter roles.When more time—six months to two years—is needed for development, some companies are experimenting with partially remote leadership roles to accommodate members of dual-career couples. Historically, this sort of arrangement has been stigmatized, as the head of HR at a global mining company explained: “Business leaders believed it signaled a lack of commitment and that people used it to simply work less.” But companies, including his own, are changing their position. “More and more people in the talent pool are asking for it, and we have the technology to make it work, so we’re a lot more open—especially when it’s likely that someone will return to their home location at the end of their assignment.” This view is supported by a growing body of research showing that people who telecommute don’t work less than their colleagues at the office. In fact, they often put in more hours and are more productive in the hours they work.

Even when companies redesign their talent strategies so that their people can expand networks, skills, and experiences in new ways, those policies often get blocked culturally. That risk is particularly high when leaders from the unbounded generation subscribe to the view that the mobility and flexibility challenges of dual-career couples are, as one executive put it, “personal things that talent should work out for themselves.” For HR’s benefit, such leaders may pay lip service to supporting members of dual-career couples—or they may genuinely believe they’re being supportive—while still, consciously or not, discouraging or punishing the use of flexible work policies.

That this exposure changes mindsets mirrors a discovery in another area of study: the finding that men whose wives have careers are less likely to discriminate against women at work and more likely to facilitate their career development. The psychological mechanism at play here is personalization. Someone who experiences “the other’s” situation firsthand is much more likely to understand it and respond in a supportive way.

Joshua, a manager in the high-potential program of a global consumer goods company and part of a dual-career couple, explained: “Word gets around the HiPo group which senior managers encourage flexible working, and we compete like crazy to get assignments with them.”

CONCLUSION

Companies must embrace a new model of talent management to attract and retain tomorrow’s leaders. When high potentials see that it’s possible to grow and advance in their organizations without sacrificing their partners’ success, they’ll feel safer opening up about their mobility and flexibility challenges. As a result, their organizations will be able to plan better for the future and make the right kinds of investments in the right people. Everyone will come out ahead.|

Training Program

INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT/IHRM

Internationalize the human resource management capabilities of HR professionals in Vietnam

Opening Date: Stember 13, 2018 in HCMC

Opening Date: Stember 20, 2018 in Hanoi Please click HERE for more information |