HOW TO WORK WITH A BAD LISTENER

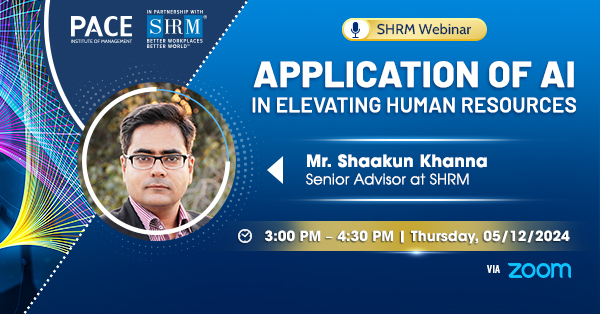

Editor's Note: SHRM has partnered with Harvard Business Review to bring you relevant articles on key HR topics and strategies. In this article, the author outlines the difficulty of working with people who do not listen.

It's a challenge to work with people — peers, junior colleagues, or even bosses — who just don't listen. Whether your colleagues interrupt you, ramble on, seem distracted, or are always waiting for their turn to talk, the impact is the same: You don't feel heard, and the chances for misunderstandings — and mistakes — rise. Are there tactics you can use to encourage your colleagues to listen better? Should you talk to them about their poor listening skills? What's the best way to deliver the message?

What the Experts Say

"Dealing with colleagues who don't listen is both hard and frustrating," says Sabina Nawaz, a global CEO and executive coach. "When someone is not fully present, it erodes the quality of what you say." The experience might, for instance, "cause you to lose your train of thought" or "suppress what you originally planned to communicate." It's also possible that "you could get derailed into the drama of why it's happening," she adds. "You might take it personally and think, 'My colleague is so arrogant.'" Potential problems aren't limited to "misunderstandings and hard feelings," according to Christine Riordan, the president of Adelphi University and a leadership coach. A colleague who doesn't listen can also "have very negative consequences from an operational standpoint — there are often a lot of mistakes because projects don't get executed correctly." So it's imperative to address the issue. Here are some strategies for working with colleagues who never seem to be listening.

Consider work styles

While some of your colleagues may be flaky space cadets who are unable to pay attention, it's also possible that they may be more visual people who have difficulty processing oral instructions. "Some people are visual and some are verbal," Riordan says. She advises "asking your colleague how they prefer to receive information. Say: 'Should we have a conversation, or would you like to see something in writing?'" Try to be a "flexible" and understanding conversation partner, Nawaz adds. "You need to use your colleague's time efficiently."

Reflect on your own behavior

Putting up with a colleague who's a bad listener often causes you to "look in the mirror" and "question whether you're a good listener yourself," Riordan says. "Bad role models are as instructive as good ones," she adds. As part of this soul-searching, it's wise to reflect on how you approach professional conversations and what you could do to improve, Nawaz says. "Maybe you're a rambling speaker. Maybe you overwhelm your listener with numbers. Maybe you need to tell more stories," she says. Take the time to "get some data on your own communication style" so that you can model the behavior you want to see.

Demonstrate empathetic listening

One way to encourage your colleagues to listen better is by practicing "empathetic listening," Riordan says. Really try to understand the other person's point of view. Nawaz recommends taking notes while your colleague is speaking — simple "one- or two-word reminders" will suffice. "Then, when there's a natural pause in the conversation, validate your colleague's main points while at the same time integrating your thoughts into the conversation." The goal, Nawaz says, is to "think about your audience" and "what's in it for them."

Highlight the magnitude of your message

Emphasizing the importance of your message up front can help as well. Before even starting a conversation, Riordan suggests saying something along the lines of: "I have something really important to talk to you about, and I need your help." This sends a signal to your colleagues that they ought to relinquish the stage and prick up their ears. "It should strengthen their awareness to listen more carefully," she says. Riordan also recommends making your point "multiple times and in multiple ways." Be open and unequivocal about what you're doing. "Say, 'I want to repeat this, because I want to make sure it's understood.'" Then you should follow up with: "Does that make sense?" That way you can "make sure what you said has been captured."

Create accountability

It's also important to hold your colleague "accountable" for listening, Nawaz says. When talking to a distracted boss, for example, she suggests letting your manager "know that she's on the hook for something" and that there is a "deliverable" that's needed by the conversation's end. You might, for instance, say: "I have three possible strategies that I want to tell you about. In the end, I'm looking for you to make a decision on one of them.'" Be explicit about your priorities, Riordan says. If you're dealing with a coworker who has a tendency to forget certain conversations, "you should set timelines to anchor" your expectations "in your colleague's mind," she says. "Say: 'That [task] is critical for this project. Do you have a date when it will be finished?'"

Show concern

Calling out the bad behavior of a colleague is generally fraught. But it can be done if you come at it from a "point of empathy" and compassion, Nawaz says. "You might say something like: 'You seem to have a lot on your plate that's requiring your attention. Is there anything I can do to lighten your load, so when we're talking you can be fully present?'" Your offer has to be genuine, of course, or it may sound like a passive-aggressive jab. And be tolerant of office distractions. If your colleague's phone keeps buzzing or dinging, and you notice their eyes moving in that direction, stop talking and say: "Do you need to check that?" Maybe the answer will be, "No, I will turn it off." Or maybe it will be, "Yes, I am expecting an important call. Can we talk later?"

Address the problem directly

If the culprit is a close colleague or a boss with whom you have an otherwise strong rapport, consider addressing the issue directly by telling them that they're not hearing what people have to say. Be sure to "cite an example where your colleague didn't listen and it had negative consequences for the team," Riordan says. But tread carefully. "You really need to have a positive relationship with the person in order for this to be effective," she adds. Otherwise, the person could just end up getting defensive.

Propose a social contract

Another option if the problem persists is to propose instituting a "social contract" that puts parameters on "how your team members interact with each other," Riordan adds. By raising it to the team level, you aren't singling out any one person but making an agreement as a group. The contract — which ought to be "updated regularly" — would stipulate that colleagues "not dominate the conversation" and give "everybody a chance to share an opinion." These contracts work best in workplaces that have a relatively strong, supportive culture to begin with. If upper management isn't on board, it's going to fall apart. "I've seen dysfunctional teams where this would not work at all," Riordan says. If your team falls into this category, avoid this shared option and instead focus on how you can improve your own individual interactions.

Principles to Remember

Do:

- Make sure your colleagues feel heard and understood by validating their points.

- Stress the importance of your message before launching into the conversation: "I have something important to say, and I need your help."

- Consider broaching the idea of a social contract for your team that would put parameters on how colleagues interact with each other.

Don't:

- Ignore your colleagues' preferences in terms of how they like to receive and process information; some people are verbal, others are visual.

- Overlook your own communication style. Reflect on how best to capture the attention of your colleagues.

- Be afraid to call out your colleague — but do so in positive terms. Say something like: "You seem distracted. Is there anything I can help you with?"

Case Study #1: Underscore the importance of your message and follow up in writing

Jim Jacobs, president of Focus Insite, the market research firm based in West Chester, Pennsylvania, once worked with a colleague — we'll call him Gary — who was not a good listener.

"Gary liked to hear himself talk," Jim recalls. "He also suffered from selective amnesia — we'd have a good meeting, develop a plan, and then he would 'forget' what we talked about."

A few years ago Focus Insite embarked on a big market-research study where it needed to recruit doctors, patients, and caregivers from all over the country who had knowledge of a specific medical condition. It was an important and lucrative opportunity; Jim could not afford any miscommunication.

"One slip-up in communication can cost our firm tens of thousands of dollars — or even millions if you consider the lifetime value of a client," he says.

Jim needed to convey to Gary how much was riding on the study. "I said: 'We have a goal of recruiting a certain number of participants by a certain date. This is really important, and we have to hit this. If we don't, there are consequences: Not only are we not going get our bonuses, but we could lose the client."

Jim then followed up with Gary through email to make sure his message got across. He laid out the project's timeline and deliverables. This is standard practice at Focus Insite. "After every meeting, whoever held it sends out a summary of what we discussed over email. We use Slack because that way, you see the whole thread."

Finally, to make sure that Gary understood what needed to be done, Jim had a "frank conversation" about the importance of strong communication. His relationship with Gary was generally good, but still, he was wary of making him defensive. "I said, 'Let me tell you about a former employee, Phil, who wasn't paying attention and once caused us to miss our deadline. We couldn't bill, and we lost the client. We learned the hard way. I'm trying to avoid a situation like that, which is why I need your help.'"

Couching it this way helped Gary feel that Jim cared about his success and the success of the company. "I wanted to show him I was looking out for him."

The project went well, and Gary has "absolutely gotten better" at listening.

Case Study #2: Show compassion and understand what motivates your colleague

Earlier in Ash Norton's career, she worked with a colleague — whom we'll call Nancy — who had difficulty paying attention.

It wasn't clear if Nancy didn't listen — or didn't want to hear what people said. "It wasn't so much that Nancy forgot things; more that they just were not a priority to her or that she didn't focus on them," says Ash, who at the time was a laboratory supervisor at a large company. "She just really thought her way was the best, easiest, or quickest."

After Nancy's failure to listen caused her to make a crucial error — "She made a mistake while logging a compliance measurement" — Ash knew something needed to be done. "It was a fairly simple error," she recalls, "but it could have had significant financial and regulatory repercussions for the company."

Before she sat down with Nancy, Ash spent time preparing what she planned to say. She reflected on what motivated Nancy and how she could encourage her to pay better attention. "I realized that a priority for Nancy was pride and recognition for her work, so by doing her own thing, she felt like she was making an impact," Ash says.

This revelation helped Ash effectively set up the conversation. "I framed the discussion so that Nancy understood that [we] recognized and appreciated her contributions — but they just couldn't be done in isolation," Ash says.

Together Nancy and Ash developed an action plan (including dates and deliverables) to help Nancy follow through on expectations. Over time, Nancy improved.

Today Ash provides leadership development for engineers. She has helped many managers encourage their colleagues learn to listen better. Her first piece of advice to them is: Listen first. "It is easy to assume that the other person isn't hearing you," she says. "But maybe they are and are just interpreting [what you said] differently. Or they have a different perspective. So make sure that you really have an open mind and are listening to the other person."

Rebecca Knight is a freelance journalist in Boston and a lecturer at Wesleyan University. Her work has been published in The New York Times, USA Today, and The Financial Times.