REDUCING ANXIETY BY HELPING EMPLOYEES DEAL WITH UNCERTAINTY

Few things cause more anxiety than the unknown, and few things generate more unknowns than our modern workplaces.

From the younger workers we interviewed, we found uncertainty was leading to a generation in perpetual angst—even before the pandemic. Ashley, a 26-year-old in financial services, told us her anxiety is tied to the stability of her company and her job. “My generation’s experience has been affected by what’s happened over the past 20 years: 9/11, people got laid off; the crash of 2008, the same thing. Now it’s AI and robots that are making our jobs unnecessary.”

While there it may seem like there’s little an individual manager can do to address the root causes of big-picture uncertainty, what they can do is communicate about challenges affecting their organization and what leadership is doing to address them, and especially how those challenges may impact their team and their priorities.

From our work coaching leaders, we developed a set of methods that leaders can use to communicate with employees to help reduce anxiety overload.

Ensure everyone knows exactly what’s expected of them (Source: freepik.com)

Method 1. Make it okay to not have all the answers.

When Lutz Ziob was general manager of Microsoft Learning, he led his team of 400 employees through a significant transformation. For years, his externally focused learning organization had made their money inside client corporations, teaching workers how to use the Microsoft toolkit. With an eye to the horizon, the debate became whether to let go of this profitable way of doing things and instead start training people in Microsoft products much earlier, in university or high school. Ziob didn’t have the answers, so he turned to his people and introduced a structured way to debate.

He asked team members to come to a series of discussions with evidence and a point of view. They were to defend their opinion vehemently and then be willing to switch sides. Chris, for instance, would argue against the change from a sales perspective, and Lee Anne in the affirmative from a marketing perspective. Then Ziob would have the two switch sides and continue the discussion. In the end, it was hard to know who won the debates. It didn’t matter.

Ziob built a team that thrived by providing the best information available and an environment for his team to analyze their future and make informed decisions as a group. To a person, his direct reports said that their leader created a learning environment where people could experiment, take risks and make mistakes. It is what allowed their team to make intelligent decisions in times of uncertainty.

Method 2: Loosen your grip in tough times.

In an interview with Nicole Malachowski, the first female pilot in the U.S. Air Force demonstration squadron the Thunderbirds, she explained how pilots fly when turbulence or headwinds occur. “It’s human nature to try to resist change. When we are flying in formation three feet apart, at 450 miles per hour, upside down, we have a contract with each other. It’s to loosen your grip. If you fly with your hand on the stick with all five fingers tight, and you try to react to every bump, you get into what we call a pilot-induced oscillation. Bigger corrections. It’s unsafe and makes things worse. That’s not how you nurture change. When things get bumpy, we lighten up on the stick, using just a few fingers.”

Unfortunately, research shows more than half of workers say their managers become more closed-minded and controlling during ambiguous, high-pressure situations. Malachowski’s analogy is a terrific way to think about leading a team through uncertainty. If we, as leaders, fight change or try to control every aspect of our employees’ work during a crisis, we’ll typically make things worse. If leaders stay loose—open and curious—they’ll be more successful in the long run and keep their teams together.

Method 3: Ensure everyone knows exactly what’s expected of them.

When employees don’t understand what is needed of them day-by-day, it’s like throwing fuel on the anxiety fire. Managers may respond to this suggestion by saying, “Of course my people know what they’re supposed to get done! They’ve got job descriptions, deliverables.” Yet time and again, team members we visit with say they suffer from a lack of clarity about what’s really expected of them or how they are doing regarding their goals.

We can attest that much anxiety stems from details about their jobs that managers often assume to be insignificant. A rule: If an employee is asking questions about minutia, they’re unfamiliar with a process. Indeed, several of our young interviewees complained about the on-the-job training they’d received, which were more overviews and not tailored to how someone in their position would use the software or follow a procedure or implement a system.

Anxiety can be ratcheted up when employees are not given enough guidance about how to achieve their goals; when no one takes the time to show them approaches that have been most effective or warn them of common mistakes to avoid; or when a manager does not help them deal with challenges that emerge. One young employee confided to us, “I would kill to have my boss take a few minutes now and then to help prioritize all that’s going on and maybe give me an idea of how much latitude I have to make my own decisions.”

Method 4: Keep people focused on what can be controlled.

Part of effective leadership is about helping workers acknowledge what they cannot change and direct their attention to what they can.

We visited once with a customer service team where employees identified the company’s antiquated system for managing workflow as a pain point. Despite that, however, the team achieved high marks for the quality of their work. The employees told us how appreciative they were of their team leader, who was effective in relieving anxiety about keeping up on the expectations for speed. She coached her workers to accept that the system was what it was, and other regions of the country weren’t any faster. She encouraged her people to redirect their attention to accuracy. She absorbed any flack from above and helped her team focus on what they could get done each day.

She said, “What we can control is our work ethic, the quality of the product we deliver, and how we treat each other and our clients.” What this boss had her people practice is called “emotional acceptance.” She didn’t try to quash feelings of stress with positive thinking, which often just makes things worse. Instead, she restructured their to-do lists to give emphasis to what they could realistically master.

Method 5: Offer constructive feedback.

The most effective leaders we met in our research were not afraid to deliver fair, tough coaching. And yet according to Forbes, nine out of 10 managers say they avoid giving constructive feedback to their employees for fear of them reacting badly. Funny that research also shows some 65 percent of today’s workers feel shortchanged when it comes to receiving individualized feedback from their bosses.

To offer constructive feedback, we coach leaders away from the commonly recommended “sandwich” approach of offering a negative between two positives. The best constructive feedback includes specific ideas for improvement, instead of generalities, along with meaningful praise in the right measure.

Constructive feedback is vital because it clarifies expectations, builds confidence that people can improve and helps team members learn from and recover from mistakes (which we all make). It’s also worth noting that with time, these conversations become less uncomfortable. When it’s the norm in a team, people don’t take correction as personally. It’s just a part of the way the group runs, which is why these one-on-ones should be positive and genuinely constructive, not intense or awkward.

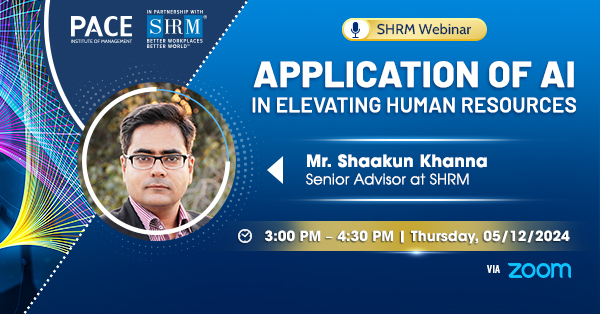

Source: SHRM.Org